Great books, like possessed people, speak in many voices. My favourite books are not about one thing: they are large (not necessarily long) and contain multitudes. Writers are guides to other worlds, and the guides I am glad to follow are smart enough to show me the coolest sights, but not so chatty as to silence my own thoughts with their talk. The ideal story will give me some anchors—I don’t think you can love Angela Carter’s The Bloody Chamber if you have no interest at all in sex and gender—while aiming for the kind of fuzzy beauty which you glimpse in dreams.

When I got to the last page of Donna Tartt’s The Secret History, I was in love. Here was a book which gave me magic as an anchor (not only magic—it was large, and contained multitudes), and talked about it with rare clarity. I had just read a one-in-a-million kind of book, and I couldn’t wait to share my thoughts with the world.

The world disagreed.

Not on the one-in-a-million-ess: saying that you love The Secret History is a bit like saying that you love fox terrier puppies. Everybody is on board. But saying out loud that you think it is fantasy? That is like saying that you love those puppies medium rare. Folks will take a step back.

Buy the Book

The Secret History

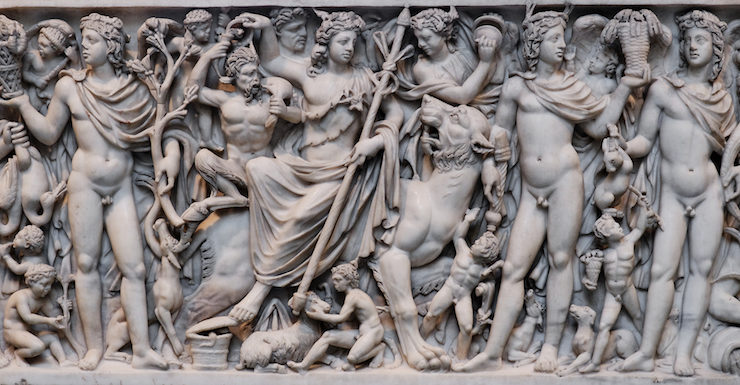

Give me a chance here: The Secret History is about magic. Explicitly so. At the heart of the story is a ritual that goes wrong because it works. Four excessively civilised students put it in their mind to invoke Dionysus, one of the wildest gods in any pantheons, but they start small, and the god does not come. They realise that they need to up their game, and they go full on with the fasting, the sex, the wine, the wild acts which are supposed to make Dionysus appear. We are in b-movie territory: these guys are the better educated equivalent of your typical horror-movie gang of young people who fool around with a Ouija board for a laugh. And then the Ouija board works.

And then Dionysus appears.

“In the most literal sense,” one of them says. Dionysus comes and he does what Dionysus does; that is, stuff that is very untamed, and thus, very dangerous. Caught up in the god’s frenzy, the four students end up killing someone. They had a domesticated idea of wildness. They didn’t know that in the wild you can die as easily as you can fuck, and ecstasy is terror as much as it is joy.

The whole story revolves around the consequences of that night. The Secret History is an exploration of what happens when primal magic irrupts into the modern world—a fantasy trope if there is one. Nowhere in the book, nowhere at all, does the story hint that magic might be a delusion. It is vague, yes, and undefined, of course, and impossible to demonstrate, surely, but we have no cause to believe it is not the real deal. “Vines grew from the ground so fast they twined up the trees like snakes; seasons passing in the wink of an eye, entire years for all I know…” It is all there, on the page.

Still, my friends took for granted that this is not a book about, or even featuring, magic. Why is that?

I think that there are enough reasons to fill a proper essay. Two of them I find compelling: the first has to do with life, the second with genre.

Life first. An orgy was part of the ritual: this much is obvious. It is easy (reassuring, even) to think that the orgy was all there was, and the ritual was only an excuse to get down. What can possibly be divine about an orgy?

Quite a lot, actually: there are myths about Dionysus punishing people for their impiety when they refuse to join his revelry. Yes, probably the students were playing at magic to get some good sex, but good sex, at times, calls down the gods. In our life, in modern times, we keep flesh and spirit neatly separated. That is not always been the case: carnal pleasure too is a form of worship. The moment we read there was an orgy, we instinctively refuse to believe there could also be magic, but the gods know better.

And then genre. The Secret History does not look, smell, and feel like a fantasy book. It was not published as such; it has a prose richer than usual; the storyline is about the mundane fallout of a single magical act; and in exploring the fallout, the story makes you forget what it caused in the first place. It pulls an inverted magic trick: rather than faking sorcery, it hides it in plain sight, lulling you into the delusion that, even though a god was invoked “in the most literal sense” and a divine maelstrom ensued, there is nothing to see here, nothing to gape at. It takes a writer of immense bravura to keep this level of understatement.

The characters of The Secret History are not the best human beings one could come across, but it is easy to resonate with their attempt to break out of the cage of a reality that was set for them before they were born. They touch something older, something wilder, something, perhaps, truer; and that thing touches them in turn, and there problems begin.

At the core of The Secret History is what Rudolf Otto called a mysterium tremendum et fascinans, a terrifying and alluring mystery. Which is, I think, a perfect definition of fantasy, both as a genre, and as the deed that makes us human.

Originally published July 2018.

Francesco Dimitri is an Italian author and speaker living in London. He is on the Faculty of the School of Life. He is considered one of the foremost fantasy writers in Italy, and his works have been widely appreciated by non-genre readers too. The Book of Hidden Things is his debut novel in English.

It is not quite true that we separate out carnal pleasure from spirituality. For instance, in Catholicism, sex between a married couple is celebrating the sacrament of marriage. We just do not normally speak of it that way.

I find the idea that generally people do not associate magic a bit astounding. Sex rituals have been associated with the supernatural for a long time and features in more adult oriented fantasy stories, like how Melisandre creates her shadow assassin for Stannis in Game of Thrones.

“saying that you love The Secret History is a bit like saying that you love fox terrier puppies. Everybody is on board. But saying out loud that you think it is fantasy? That is like saying that you love those puppies medium rare. Folks will take a step back.”

Wonderful!

Glad to see that someone gets the magic underpinnings of The Secret History. It didn’t really click for me until a recent re-read.

Incidentally, The Book of Hidden Things was a great read.

I always thought this about The Secret History. Glad to finally see someone agree

Off the top of my head I can’t think of a worse god to summon up. At least not in the classical pantheon. Did these kids ever take a class in mythologyl

Wonderful article and one I can full heartedly agree with. The book seemed to resonate people as a detective novel wherein you know the culprit (s) but not the why. It was inexplicably, magic and the calling of the gods. ‘The Secret History’ is still one of the greatest novels I have ever read.

@1, Crusader75 It is not quite true that we separate out carnal pleasure from spirituality. For instance, in Catholicism, sex between a married couple is celebrating the sacrament of marriage.

I don’t think that’s not unique to Catholicism. I believe it’s true of all religions that sacralize marriage–which is to say, all major religions.

I read this years ago – and I think I remember another curveball throwaway that hints that this not exactly our reality. Isn’t one of the students at Hampden the princess from a fictional Mid East country that is the home of the Tower of Babel,which exists as an actual historical construct like the Great Pyramids or Stonehenge.